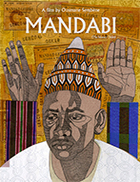

Mandabi [Blu-Ray]

|

Mandabi (The Money Order), the second of Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène's feature films, is a landmark of sub-Saharan African cinema. Although Sembène had already made the well-received short film Borom Saret (The Wagon Driver, 1963) and the feature Black Girl (Le noire de …, 1966), which won the French Prix Jean Vigo (which had previously been given to films by Claude Chabrol, Jean-Luc Godard, and Alain Resnais), Mandabi was a different kind of achievement because it was a genuinely African film. Unlike Black Girl, which was set in France and featured a largely European cast, Mandabi is set in Dakar, all the characters are Senegalese, and, importantly, they all speak Sembène's native Wolof language. It is very much a film about postcolonialism, a theme central to both Borom Saret and Black Girl, although here the focus being on the residual effects of Western imperialism on the African experience. Before he became a filmmaker, Sembène was a novelist, and many of his early films were adaptations of his own works, most of which were originally published in French. Recognizing that French-language novels had little chance of reaching most Senegalese people, many of whom were illiterate, much less fluent in French, he used the cinema to expand his reach, translating those stories into a visual medium that spoke directly to the African viewer's experience in the language they spoke. Like his earlier films, Mandabi was based on one of Sembène's novels, in this case the 1966 novella Le mandat (The Money-Order), which the film follows closely in telling the story of Ibrahim Dieng (Makhouredia Gueye), a relatively ordinary middle-aged Senegalese man who receives a money order from his nephew, who works as a street cleaner in Paris, and then spends the rest of the film trying to cash it. Like many African, Asian, and South American filmmakers, Sembène was heavily influenced by Italian neorealism, especially that movement's focus on everyday lived experience and the inherent dignity of ordinary human life, which is reflected in the surface simplicity of the plot that nevertheless reveals a wealth of detail about the difficulties imposed by Western norms on African life, the residue of French colonialism on Senegal (which had become an independent nation only eight years earlier). Sembène's style is direct and unadorned, and although the film was shot in color (a decision that Sembène made somewhat reluctantly), the cinematography by Paul Soulignac, who shot Agnès Varda's La Pointe Courte (1955), feels documentary-like. Ibrahim learns of the money order from his two wives, Méty (Ynousse N'Diaye) and Aram (Isseu Niang), who receive word of it from the postman. The money order is for 250 francs, and he is to cash it and then distribute the money among himself, his nephew, and his sister. The money order is something of a windfall for Ibrahim, who has been unemployed for four years and has two wives and seven children to support. Yet, all his attempts to cash this money order—a seemingly simple task—runs headlong into obstacle after obstacle, most of which are bureaucratic and fundamentally alien to Ibrahim's understanding of the world. For example, he is required to show an official identification card to prove his identity, something that is absurd to him since he is used to living in a neighborhood where everyone knows who he is—why would he have to prove to someone he is who he knows is and everyone he knows knows he is? In order to secure an identity card, he has to produce a birth certificate, something he not only does not have, but does not know how to attain from the proper government office because he is not entirely sure in what year he was born. Various people try to assist him in his efforts, while others (including neighbors and relatives) come out of the woodwork looking to borrow money or otherwise profit from his good fortune. In this regard, the film is decidedly pessimistic in its outlook on humanity (much like Black Girl, which dramatized in no uncertain terms how a person could be reduced to an object), as Sembène emphasizes the flaws and dishonesty and simple lack of caring of those around Ibrahim, which essentially dooms his efforts to failure. The only fundamentally good character we see is the nephew, Abdu (Mouss Diouf), who sends the money order out of decency, but without the necessary foresight of recognizing that Ibrahim would be unable to cash it. Which brings us to Ibrahim himself, who is an engaging protagonist, but hardly an admirable one. Overly impressed with himself and his patriarchal authority (he has no qualms about lording over his wives, who endure it and then go about their business when he leaves), we often see him indulging himself in food and self-care (the film's opening scene shows him getting a meticulous shave and facial from a street vendor) and he wears his brightly colored boubou (a traditional long, flowing garment) with a sense of pride that separates him from so many others who have adopted Western-style clothing. He is a bit of an absurd figure, hoisting up his patriarchal pride despite his poverty and lack of employment, but we still feel for him and his predicament. Makhouredia Gueye was a theater actor making his screen debut, and he would go on to only a handful of other film roles, including Sembène's Xala (1975) and Ceddo (1977). He has a strong, boisterous presence that is both comical and endearing, which is central to the film's fundamental effectiveness. Ibrahim is who he is and mistakenly believes that he can navigate a postcolonial bureaucracy in the same way he does his neighborhood, which sets up a conflict of cultures that is fundamentally at an impasse, the kind that ensures that men like him will always remain on the lower rungs of the social and economic ladder.

Copyright © 2021 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © The Criterion Collection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)

Subscribe and Follow

Get a daily dose of Africa Leader news through our daily email, its complimentary and keeps you fully up to date with world and business news as well.

News RELEASES

Publish news of your business, community or sports group, personnel appointments, major event and more by submitting a news release to Africa Leader.

More Information